Now imagine that that happens every day

through simple activities like having a shower, or walking to the

shop and recovery is always incomplete. The thing is chronic fatigue

isn't just tired limbs it is far more insipid, affecting every part

of the body. I'll start with the obvious and then get down to the effects that you might not expect.

|

| The NHS Choices website uses this as their picture for fatigue. It's not completely inaccurate. |

Limbs

As described above, limbs are the most

obvious areas affected by fatigue, something most people are familiar

with. Limbs that feel heavy and tired; muscles feel weak; doing

anything feels like an effort; the muscles might hurt and ache;

joints hurt; there may be pins and needles or numbness.

Depending on how severe it is this

might mean slower movement, some unsteadiness, or even difficulty

with smaller movements like making a cup of tea.

Core Muscles

The next easiest to comprehend is

fatigue of the core muscles. I'm including abdominal, back and neck

muscles here. You might have experienced fatigue of the core muscles

following a work out session or if you have neck or back pain.

As above the muscles become painful or

achey, feel tender to touch and are generally tired.

Fatigue of the core muscles means that

holding a good posture is difficult, which can further exacerbate

pain and discomfort. It can become difficult to sit upright or hold

your head up without support.

Smaller muscles

Hands, fingers, feet, facial muscles.

All those little muscles that we use almost without thinking. They

react just like limb muscles. Aching and weak, slow to move. In the

hands this can make holding things difficult so I have to stop

knitting or put down my book, maybe use two hands to cradle a cup of

tea instead of holding the mug by the handle. With the facial muscles

this can make expressions and speech difficult, droopy eyelids and

week smiles. In me this is often accompanied by partial paralysis of

my face and/or numbness or tingling.

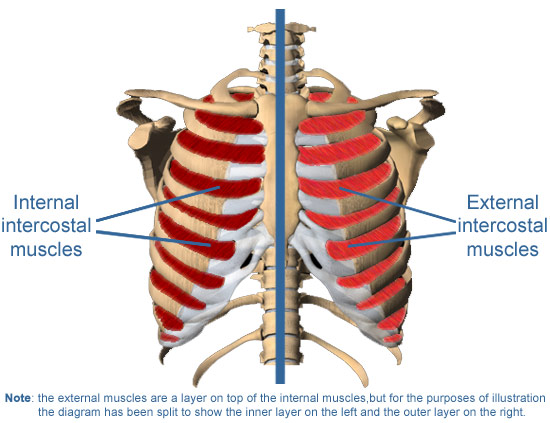

|

| picture from www.medguidance.com |

Intercostal muscles and Diaphragm

Your intercostal

muscles sit between your ribs and are responsible for lifting and

expanding the chest. They come in several sets and all can become

fatigued. The thoracic diaphragm is the broad sheet of muscle at the

base of our ribs, separating the lungs from the abdominal organs

(along with a load of membranes). The diaphragm is also crucial in

the mechanical act of breathing, contracting and relaxing to allow

air in and out of the lungs.

The limbs and

core muscles are the more obvious targets of fatigue as we see them

physically doing something. We can see and feel when our legs are

moving, when we are bending and stretching; that these muscles become

fatigued makes sense.

The intercostal

muscles however are less noticed. Their movement is for the most part

involuntary. As long as we are breathing they are moving. We might

suppose then that if we do something that increases the breathing

rate then the diaphragm and intercostal muscles will work more and

therefore become fatigued. This is only part of the story. In reality

they are working all the time and thus using energy all the time.

Limbs and core

muscles may be first to show the affect of fatigue however, if the

fatigue becomes extreme before you are able to get any rest or

recharge, then intercostal muscles and diaphragm can become affected.

This means that breathing can become laboured, the chest hurts and

feels heavy or like somebody is pressing down. Laboured breathing has

never helped anybody feel more refreshed.

The digestive system

Your mouth and

jaw are made up of muscles which must chew and move food. Then you

need to swallow, employing your tongue, soft palate and throat to

move chewed food down your digestive tract in to your stomach and

gut. The stomach contains layers of smooth muscle used to churn the

food as it digests, it is guarded by two sphincters (top and bottom)

rings of smooth muscle that control the flow of food matter into and

out of the stomach. Once the food has been broken down in the stomach

it passes into the small intestine, and then into the large

intestine, long tubes of specialised tissue and smooth muscle.

These muscles move involuntarily, we can't consciously control them but, they do move a lot. They move to break down the food and to keep it moving so that proper digestion can occur. They move to stop blockages occurring and to prevent food from 'backing up'.

These muscles move involuntarily, we can't consciously control them but, they do move a lot. They move to break down the food and to keep it moving so that proper digestion can occur. They move to stop blockages occurring and to prevent food from 'backing up'.

When a body

becomes seriously fatigued these functions can slow down. Just as

limbs can become sluggish and slow moving, unreliable and weak, the

smooth muscles of the gut and the muscles of the throat and mouth can

become unreliable. This makes eating not just difficult but

dangerous.

'Too tired to

eat' doesn't just mean I am too tired to make myself some food, or too

tired to lift a slice of pizza to my mouth, it can mean I am too

tired to chew. That my throat is too fatigued to swallow efficiently

and choking or gagging is a real risk. It can mean that my digestive

system isn't functioning efficiently and food is just sitting there.

Nutrients aren't being absorbed, worsening the fatigue, and waste

material isn't being processed correctly.

The Heart

OK I'm going to

confess, I haven't personally experienced this but it is something

that concerns me. If everything else can get fatigued, why not that

hard working muscle the heart? Maybe that's not possible or likely

but if you have some information about this let me know.

Now, not all of

these things happen every time I get fatigued. It's a sliding scale:

first the limbs and muscles which have been directly affected get

tired, then my core muscles get tired and I slump. My facial muscles

get tired and it is difficult to talk properly. By this point I am

usually in some sort of forced rest simply because I can barely sit

upright any more. But if I continue to push through and exert myself,

then I start finding breathing tough, and only in extreme

circumstances do I find eating/digesting a difficulty. But this is all fatigue.

This is all the result of the chronic fatigue caused by CFS/ME and other illnesses such as Chronic Lyme Disease, Rheumatoid Arthritis, and Lupus to name but a few.

This is 'just'

the physical fatigue. CFS/ME and other

similar illnesses can also cause a myriad of other physical symptoms

as well as cognitive fatigue known as brain fog.

Fatigue isn't

just tired. Fatigue is much much more.

No comments:

Post a Comment