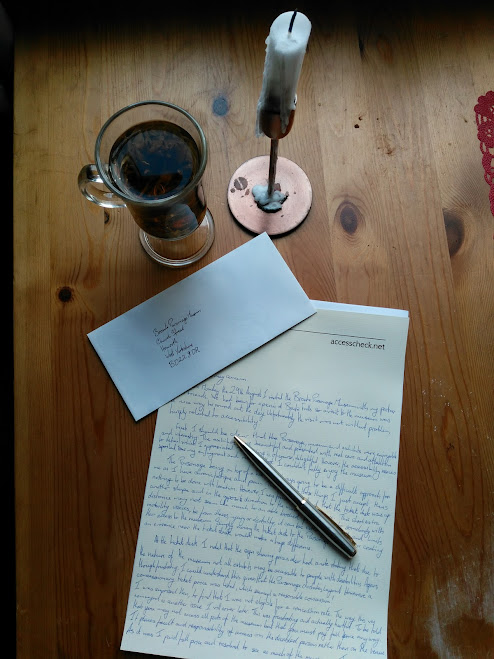

Following my Open Letter to the Brontë Parsonage Museum, I have had a response from them. I received a long letter yesterday in full reply - no standard template here. I won't be copying out the whole letter here but I do want to share some of it's content's with you because it was an excellent reply and just the sort of response I would hope to receive from a company following complaint about their accessibility.

First of all, the responded, and in full without it being a pro-forma response. That in itself raises them up above some others.

After some preliminaries, the letter opens with an apology. A genuine and full apology, without excuse or couching.

"Please let me first express my sincere regret that your visit on 29th August 2019 was blighted by limitations to the access we offer for people with disabilities, and also by the rudeness of one of our members of staff."

This is such an important thing and I can't thank them enough for doing this. So often we see non-apologies, apologies which try and shift blame on to the person complaining or which come with excuses hanging on them. An actual plainly written apology means so much. It is a sign of respect. It is a sign that they have actually read or listened to the issue and care about the person making the complaint. When you are disabled, to be treated with respect and not brushed of or belittled is so important and sadly doesn't happen as often as we would like.

The letter then goes on to state that they are speaking formally with the member of staff I named and that they [the staff member] will be included in the next session of disability awareness training. This is followed for an apology for her manner towards me and my companions.

From my point of view this is reassuring. Again the apology shows respect for the situation and to me personally and the clear statement of how it was dealt with let me know that it is something which will be remedied at the source. It's also pleasing to note that there is regular staff wide disability awareness training - this is only a minor surprise as, as I noted in my original letter, other members of staff were helpful and there was a clear indication of awareness of accessibility throughout the museum.

The paragraph continues with a discussion of their concession policy, which was central to my conflict with the staff member:

"...your visit does highlight a possible shortcoming in this policy when it comes to welcoming people with disabilities ..."

and

"I am currently putting together a comprehensive Access Report on the Parsonage Museum and its services..."

Acknowledging that there could be an issue with current policy is great. It would have been easy for them to attempt to defend their policy as "good enough" or that it being correct excused the staff member's attitude. They did neither of these things and instead have shown an interest in reviewing and improving, as well as noting the specific action that they will take.

The letter continues with discussion of the other issues I raised such as the distance between ticket desk and entrance and lack of toilets. Here there is less in the way of specific action being noted but, considering we are now talking about structural changes, that's understandable. The letter does describe some of the decision making processes behind the current set up which could have begun to sound like an excuse of defensiveness. However, it was concluded by promises of review, looking at other options and ongoing work. Though no specific details could be given, it does state that there are plans going through for development of the site which will include accessibility changes and will improve the situation. The timeline sadly is 5-10 years but, considering this involves a number of trusts and heritage funds as well as councils and local government that is to be expected.

So why am I so pleased with this?

Well firstly good communication means so much. Good communication can sometimes be responding quickly, but it can also be taking the time to be able to respond in full with all the facts. A thorough letter that properly addresses the situation is better that a quick phone call or standardised courtesy reply.

Secondly it really does address and answer each of the issues raised. It shows a level of thought and care for the subject at hand. Accessibility is all to often not properly thought through and not given the attention it needs. For somebody at the Brontë Society to actually give the issues this attention is a good thing. It also lets me know that even if they weren't previously, there is now somebody there who will make sure accessibility is given the consideration it needs.

And finally it was honest. An honest reply is so valuable. None of us our perfect not visitors and blogger, not Societies and management groups. We make mistakes or do things in a way that is less that ideal. It can be difficult when we have misstepped to own up to it, either out of pride or embarrassment. But an apology isn't just about somebody taking blame, it also validates the concerns of victim. It means that things are being taken seriously, and whilst something may not matter to you, it certainly mattered to the person who complained.

Incidentally, I should apologise to the Brontë Parsonage Museum for the tone of my letter, I know on occasion I can get caught up in the moment and obviously this is a very personal topic for me. That doesn't excuse haughtiness though. Sorry about that.

I should point out that I was also offered a free guided tour with a friend which I will be taking them up on. It's a lovely gesture but really, it's the quality of the letter that is important.

Take note, this is both how you apologise and how you address accessibility issues.

But then, they are a literary society. You'd expect a good letter.

Tuesday, 20 September 2016

Saturday, 10 September 2016

All over the internet!

Hello there! Axes n Yarn is my general blog. I've had it for several years and it's the place for writing about everything from vegan food to LARP to politics and of course accessibility. It's all a bit informal here and a place for me to get my thoughts and ideas out as well as sharing my experience with you.

However I have two other websites which might be of interest to you, especially if you like my posts on accessibility or LARP.

The first site Access:LARP is specifically there, as the name suggests, to provide accessibility advice for LARP organisers and disabled LARPers.

There are several Accessibility in LARP Guides available for download (as first featured on this blog) as well as opportunities to ask questions and even book training or consultation.

Access:Check is there for event organisers and venue managers outside of the LARP world. Through Access:Check I provide consultations and guidance on accessibility for everything from interactive theatre to art galleries. I also offer training days for groups who need to learn more about accessibility in general or tailored to a specific part of your event for example writing or choosing venues.

And if you really want to you can follow me on instagram @spoonieskeleton (where I blog about daily life as a spoonie and other chronic illness stuff plus the occasional bit of knitting) and on Twitter @Skelakit (where I tweet about anything and everything including #outofcontextrpg)

However I have two other websites which might be of interest to you, especially if you like my posts on accessibility or LARP.

Access:LARP

The first site Access:LARP is specifically there, as the name suggests, to provide accessibility advice for LARP organisers and disabled LARPers.

There are several Accessibility in LARP Guides available for download (as first featured on this blog) as well as opportunities to ask questions and even book training or consultation.

Access:Check

Access:Check is there for event organisers and venue managers outside of the LARP world. Through Access:Check I provide consultations and guidance on accessibility for everything from interactive theatre to art galleries. I also offer training days for groups who need to learn more about accessibility in general or tailored to a specific part of your event for example writing or choosing venues.

And if you really want to you can follow me on instagram @spoonieskeleton (where I blog about daily life as a spoonie and other chronic illness stuff plus the occasional bit of knitting) and on Twitter @Skelakit (where I tweet about anything and everything including #outofcontextrpg)

Wednesday, 7 September 2016

The Language of the Paralympics

This post is really a PSA to be mindful of how you think and talk about the Paralympics and Paralympians. It is a reminder, primarily, that Paralympic athletes have lives outside of the games and that the games exist in a world with many other disabled people living normal lives.

Paralympic athletes are, without doubt, awesome people and awesome athletes. They have gone through selection, trained and competed at the highest level in their sports and categories. They have worked hard and are incredibly skilled.

They are also

1. Not representative of all disabled people

2. Not fakers

3. Not there for pity or condescension

4. Actually real people.

When talking about disabled athletes people often fall fowl of a few cliches that can be at best annoying and at worst actually create a culture which causes harm to disabled people including those athletes you are talking about. That's just the cliches and comments that are supposed to be positive.

So lets take a look at them.

The truth of the matter is we could say this about anybody, able bodied or disabled. If they can be a premiership footballer, there is no excuse that you earn minimum wage. If they can run a 9 second 100 meters then there is no excuse for you to be driving to the shops. If they can swim 7 different races in the Olympics then there is no excuse for you to struggle at the gym.

The truth is that we are all different. It's as simple as that. Able bodied or disabled we are all different. We have different skills and interests. We have different abilities. We have different physiology. We have different opportunities.

However this accusation is more likely to get levelled at disabled people during the Paralympics than at anybody else. If they can do it why can't you. As well as the myriad of reasons that anybody has, from opportunity to desire, for not being a top flight athlete we also need to consider that people with disabilities are also dealing with the complexities of their health and body. The categories of the Paralympics are very clearly defined and it may simply be that any given person's disability does not neatly fit in to one of those categories. Further more, there are things that just aren't covered at all and are outside of those category's scope.

There are dozens of disabling symptoms including but not limited to chronic pain, chronic fatigue and chronic migraines that simply do not lend themselves to sports and would make it impossible to compete safely. This is especially so for people whose conditions are variable. A person who has cerebral palsy has cerebral palsy every day. A person who has chronic pain may find that today is a worse pain day than yesterday and can not simply take more pain killers to be able to compete.

The Paralympics is just as rigorous when it comes to drug testing and banned substances as the Olympics. Athletes can apply for medical exemptions, but even when granted there will be restrictions as to what dose a person can take. This can mean that some people simply wouldn't be able to compete.

Finally we have to consider false equivalency. Even if you are a top athlete and all you do is train and compete, there is some flexibility in your schedule. You can plan the number of training sessions, how long they last and when they are. You probably also have a guaranteed income of some sort or financial security. A training session is not the same as having to do a full time job. The stresses on the body are vastly different and for the vast majority of jobs, the employer has little control over where it is and what they do when they get there. Holding down a full or even part time job in a manner that is able to provide a living is physically very different from managing a training schedule and competing. That's without considering the amount of support somebody may have.

Consider a race. The athlete is driven to the track so they can conserve energy. They are provided with nutritionally balanced snacks and hydration. They have an assistant with them who can help explain things clearly, who can carry things for them. There is a rest and seating area as well as a warm up area that allows athletes to prepare in their own manner. They do the race. Maybe they win, afterwards they have help walking away, packing up their things. They are driven home. They are given time to rest and recover.

Athletes work very hard. That is without question, but how they work hard is very different from your average working life. They just don't compare. So we shouldn't compare.

"That person can race" does not equal "so any disabled person can work".

The second issue, the baggage, relates to language and attitudes that disabled people often have to face. This is the attitude that disabled people are somehow amazing simply for going about their every day lives. That to be disabled is so limiting and so unimaginable that to do anything at all is some how a superhuman feat. As previously, of course what Paralympic level athletes do is amazing and really is something to applaud, just like we are amazed by the feats of any world class athlete. The issue comes that many disabled people are so used to hearing words like superhuman, amazing, awesome in a patronising voice relating to merely living their lives that to hear it at all directed at a group of disabled people is to make us bristle. We can't be sure that every time it is being used it is because they are amazing athletes or because the speaker or writer is astounded that disabled people can do anything at all.

These phrases, and the issue with them, closely follow on from the previous paragraph. Watching somebody do something brilliant really can be inspiring and we really can feel an empathetic rush of joy when somebody has achieved something they have been striving toward. That's fine, it's normal it's not a problem. the problem comes when this language is so often used toward disabled people and so often in tones that sound like the person is speaking to a small child or a dog. There is a sense, once again, that anything a disabled person does is a shock and a pleasant surprise to some people. Additionally the language often presumes that the disabled person has done these wonderful things for the edification of the general public and not because the person just wanted to. If you find yourself thinking these things ask yourself, would you have been inspired if an able bodied person had done it? Why is it inspiring to you?

For example are you inspired by Michael Phelps winning his 28th Olympic medal? Because that's an amazing achievement and a display of truly awesome talent and training. If seeing that doesn't make you feel inspired but seeing a swimmer with muscular dystrophy get a personal best does then perhaps your inspiration is more routed in your understanding of the person's disability than in their athleticism. (I still think somebody getting a PB in a race is great to see though).

If your answer is that it's "just so good to see somebody overcoming adversity" and you don't believe that has anything to do with disability then stop and reconsider. That phrase has two main fallacies.

Firstly you are making a lot of assumptions about their disability: you don't know how much adversity that individual felt they actually had to battle through. For some it may not have felt like adversity at all. It's simply their life. It assumes that things must have been terrible for that person simply because of their disability and that they had to overcome it. That's simply not true. (And to go back to the first section, it also neglects to remember that people are competing against people in the same classification).

Secondly it means that you are drawing your inspiration and your good feeling from somebody else's perceived suffering. Just think on that. You don't find somebody inspiring or heart-warming unless they have first suffered so that they can overcome it in a way that you find pleasing.

Additionally it's also terribly patronising. It diminishes the effort and hard work that these athletes have put in to reaching the Paralympics and implies instead that they are only worth accolade because they have achieved something while disabled. I just want to pause a moment to talk about the many sports in the Paralympics and Olympics as well as, again, the huge array of classification systems. Because some able bodied people may say "Well yeah, but they're [the disabled athletes] are never going to be able to compete with normal athletes." and after I had been held back by a group of burly folk and prevented from assaulting the unsuspecting individual with my walking cane, I would explain that, actually there's often a good reason for that. So, many of the classifications take in to account an athletes physical limitation in terms of top speed achieved, or endurance. These are usually race type sports like swimming and running. In these cases, no, most Paralympians can't compete in the same races as their able bodied counterparts. Their top speeds just aren't making the qualification times that allows them to do so. However the Olympics and Paralympics aren't just about running and swimming, no not even about cycling. There are 22 different sports many of which consist of a number of different events in this years Paralympics, from para-triathlon to boccia, athletics to archery. Many of the classification and different events differ from their able bodied counterparts due to adaptations and accommodations, not because the athletes are less able (stay with me) in terms of athleticism. There are some sports where the main difference is changes to the rules around stance and equipment or specific differences in equipment that would not be allowed in the Olympic rules. These might be changes in saddle type in the Para-dressage changes, in how a sail is winched or what maximum dimension of boat is allowed in the sailing or, how many bounces of the ball are allowed in tennis Then of course there are the unique para-sports of boccia, wheelchair rugby, and seated volleyball.

Yes they are inspiring athletes but it's because of their athleticism and skill in their sports and not because they have managed to get into a world class, highly regarded renowned internation sports tournament "despite their disability."

Firstly, though the athletes may not be able to hear you (though they can hear the commentators and see the billboards) they are still real people and things aren't offensive/patronising/inaccurate/hurtful just because the person can't hear you. If you wouldn't say it to their face, don't say it.

Secondly it's because, though disabled people aren't one homogeneous hive-mind, we are still a large group of people who do have a lot of shared experiences. Sadly a lot of those shared experiences are pretty negative and are to do with being mistreated at everything from a government to a personal everyday level. This sort of language, whether from you at home on your sofa or from a commentator on prime time TV just supports that. It dehumanises and others. It belittles and patronises. It is a constant trickle of treating disabled people like crap and like they are lesser than able bodied people. If you say these things unchallenged once, it gives you silent consent to say it again. And If you say it in private the first time maybe next time you'll say it directly to a disabled person. If it is said enough and by enough people it creates a society that tacitly agrees and condones that disbaled people are just something slightly less and something slightly inferior to abled bodied people. That's the sort of society that then thinks it's ok to treat disabled people badly because after all we're not like you.

That's a big reason.

Paralympic athletes are, without doubt, awesome people and awesome athletes. They have gone through selection, trained and competed at the highest level in their sports and categories. They have worked hard and are incredibly skilled.

They are also

1. Not representative of all disabled people

2. Not fakers

3. Not there for pity or condescension

4. Actually real people.

When talking about disabled athletes people often fall fowl of a few cliches that can be at best annoying and at worst actually create a culture which causes harm to disabled people including those athletes you are talking about. That's just the cliches and comments that are supposed to be positive.

So lets take a look at them.

If they can run/swim/race/compete there's no excuse

This is possibly one of the more harmful cliches that comes out. Occasionally it is said with malice, an accusation leveled at "fakers", disabled people who can't work due to disability, but often it is said in a way that is supposed to be inspiring and encouraging to a disabled person.The truth of the matter is we could say this about anybody, able bodied or disabled. If they can be a premiership footballer, there is no excuse that you earn minimum wage. If they can run a 9 second 100 meters then there is no excuse for you to be driving to the shops. If they can swim 7 different races in the Olympics then there is no excuse for you to struggle at the gym.

The truth is that we are all different. It's as simple as that. Able bodied or disabled we are all different. We have different skills and interests. We have different abilities. We have different physiology. We have different opportunities.

However this accusation is more likely to get levelled at disabled people during the Paralympics than at anybody else. If they can do it why can't you. As well as the myriad of reasons that anybody has, from opportunity to desire, for not being a top flight athlete we also need to consider that people with disabilities are also dealing with the complexities of their health and body. The categories of the Paralympics are very clearly defined and it may simply be that any given person's disability does not neatly fit in to one of those categories. Further more, there are things that just aren't covered at all and are outside of those category's scope.

There are dozens of disabling symptoms including but not limited to chronic pain, chronic fatigue and chronic migraines that simply do not lend themselves to sports and would make it impossible to compete safely. This is especially so for people whose conditions are variable. A person who has cerebral palsy has cerebral palsy every day. A person who has chronic pain may find that today is a worse pain day than yesterday and can not simply take more pain killers to be able to compete.

The Paralympics is just as rigorous when it comes to drug testing and banned substances as the Olympics. Athletes can apply for medical exemptions, but even when granted there will be restrictions as to what dose a person can take. This can mean that some people simply wouldn't be able to compete.

|

| That's me, a disabled person, horsriding AKA doing a sport. I am not an Olympian |

Consider a race. The athlete is driven to the track so they can conserve energy. They are provided with nutritionally balanced snacks and hydration. They have an assistant with them who can help explain things clearly, who can carry things for them. There is a rest and seating area as well as a warm up area that allows athletes to prepare in their own manner. They do the race. Maybe they win, afterwards they have help walking away, packing up their things. They are driven home. They are given time to rest and recover.

Athletes work very hard. That is without question, but how they work hard is very different from your average working life. They just don't compare. So we shouldn't compare.

"That person can race" does not equal "so any disabled person can work".

They are "superhuman"

This is a little more difficult to explain. Describing athletes as a superhuman isn't reserved for paralympic athletes, it's a term given to many top flight athletes, because after all they are doing and achieving things beyond most of our wildest dreams. However, when it is used for Paralympians the term can be "othering" or have other baggage attached. Many people with disabilities have experienced being treated as some how less than human or subhuman. Whilst superhuman is more flattering than subhuman, it still serves to describe paralympic athletes as something other than a normal human being. This effect is amplified when you refer to an entire group of people as "superhuman" rather than individuals. Advertisers and commentators may be intending that group to be "Olympic level athletes" which would be appropriate, but this group also shares another characteristic, that of being disabled. Even if it doesn't rub disable people's (both athletes and non-athletes) up the wrong way, it does subtly enforce the idea in the minds of the general public that disabled people are a group of "other" and that other is different to normal humans.The second issue, the baggage, relates to language and attitudes that disabled people often have to face. This is the attitude that disabled people are somehow amazing simply for going about their every day lives. That to be disabled is so limiting and so unimaginable that to do anything at all is some how a superhuman feat. As previously, of course what Paralympic level athletes do is amazing and really is something to applaud, just like we are amazed by the feats of any world class athlete. The issue comes that many disabled people are so used to hearing words like superhuman, amazing, awesome in a patronising voice relating to merely living their lives that to hear it at all directed at a group of disabled people is to make us bristle. We can't be sure that every time it is being used it is because they are amazing athletes or because the speaker or writer is astounded that disabled people can do anything at all.

"They're so inspiring"

They're so inspiring! She's an inspiration to us all! It's so uplifting to see this!These phrases, and the issue with them, closely follow on from the previous paragraph. Watching somebody do something brilliant really can be inspiring and we really can feel an empathetic rush of joy when somebody has achieved something they have been striving toward. That's fine, it's normal it's not a problem. the problem comes when this language is so often used toward disabled people and so often in tones that sound like the person is speaking to a small child or a dog. There is a sense, once again, that anything a disabled person does is a shock and a pleasant surprise to some people. Additionally the language often presumes that the disabled person has done these wonderful things for the edification of the general public and not because the person just wanted to. If you find yourself thinking these things ask yourself, would you have been inspired if an able bodied person had done it? Why is it inspiring to you?

For example are you inspired by Michael Phelps winning his 28th Olympic medal? Because that's an amazing achievement and a display of truly awesome talent and training. If seeing that doesn't make you feel inspired but seeing a swimmer with muscular dystrophy get a personal best does then perhaps your inspiration is more routed in your understanding of the person's disability than in their athleticism. (I still think somebody getting a PB in a race is great to see though).

If your answer is that it's "just so good to see somebody overcoming adversity" and you don't believe that has anything to do with disability then stop and reconsider. That phrase has two main fallacies.

Firstly you are making a lot of assumptions about their disability: you don't know how much adversity that individual felt they actually had to battle through. For some it may not have felt like adversity at all. It's simply their life. It assumes that things must have been terrible for that person simply because of their disability and that they had to overcome it. That's simply not true. (And to go back to the first section, it also neglects to remember that people are competing against people in the same classification).

Secondly it means that you are drawing your inspiration and your good feeling from somebody else's perceived suffering. Just think on that. You don't find somebody inspiring or heart-warming unless they have first suffered so that they can overcome it in a way that you find pleasing.

Additionally it's also terribly patronising. It diminishes the effort and hard work that these athletes have put in to reaching the Paralympics and implies instead that they are only worth accolade because they have achieved something while disabled. I just want to pause a moment to talk about the many sports in the Paralympics and Olympics as well as, again, the huge array of classification systems. Because some able bodied people may say "Well yeah, but they're [the disabled athletes] are never going to be able to compete with normal athletes." and after I had been held back by a group of burly folk and prevented from assaulting the unsuspecting individual with my walking cane, I would explain that, actually there's often a good reason for that. So, many of the classifications take in to account an athletes physical limitation in terms of top speed achieved, or endurance. These are usually race type sports like swimming and running. In these cases, no, most Paralympians can't compete in the same races as their able bodied counterparts. Their top speeds just aren't making the qualification times that allows them to do so. However the Olympics and Paralympics aren't just about running and swimming, no not even about cycling. There are 22 different sports many of which consist of a number of different events in this years Paralympics, from para-triathlon to boccia, athletics to archery. Many of the classification and different events differ from their able bodied counterparts due to adaptations and accommodations, not because the athletes are less able (stay with me) in terms of athleticism. There are some sports where the main difference is changes to the rules around stance and equipment or specific differences in equipment that would not be allowed in the Olympic rules. These might be changes in saddle type in the Para-dressage changes, in how a sail is winched or what maximum dimension of boat is allowed in the sailing or, how many bounces of the ball are allowed in tennis Then of course there are the unique para-sports of boccia, wheelchair rugby, and seated volleyball.

Yes they are inspiring athletes but it's because of their athleticism and skill in their sports and not because they have managed to get into a world class, highly regarded renowned internation sports tournament "despite their disability."

But why is this important?

Well for a couple of reasons.Firstly, though the athletes may not be able to hear you (though they can hear the commentators and see the billboards) they are still real people and things aren't offensive/patronising/inaccurate/hurtful just because the person can't hear you. If you wouldn't say it to their face, don't say it.

Secondly it's because, though disabled people aren't one homogeneous hive-mind, we are still a large group of people who do have a lot of shared experiences. Sadly a lot of those shared experiences are pretty negative and are to do with being mistreated at everything from a government to a personal everyday level. This sort of language, whether from you at home on your sofa or from a commentator on prime time TV just supports that. It dehumanises and others. It belittles and patronises. It is a constant trickle of treating disabled people like crap and like they are lesser than able bodied people. If you say these things unchallenged once, it gives you silent consent to say it again. And If you say it in private the first time maybe next time you'll say it directly to a disabled person. If it is said enough and by enough people it creates a society that tacitly agrees and condones that disbaled people are just something slightly less and something slightly inferior to abled bodied people. That's the sort of society that then thinks it's ok to treat disabled people badly because after all we're not like you.

That's a big reason.

Friday, 2 September 2016

An Open Letter to the Brontë Parsonage Museum

To Whom it May Concern,

On Monday the 29th of August I visited the Brontë Parsonage Museum with my partner and friends. We had been for a picnic at Brontë Falls so a visit to the museum was a nice way to round out the day. Unfortunately the visit was not without problem, largely related to accessibility.

First I should be clear that the Parsonage, museum and exhibits were enjoyable and interesting. The exhibits were beautiful and presented with real care and attention to detail that I appreciated. The setting is, of course, delightful. However, the accessibility issues spoiled my enjoyment and meant that I couldn't fully enjoy the museum.

The Parsonage being on top of a hill was always going to be a difficult approach for me as I have issues with chronic pain and fatigue. This is one of those things you just accept, there's nothing to be done with location. However, I was frustrated to find that the ticket desk was up another slope and in the opposite direction to the Museum entrance. This short extra distance may not seem much to an able bodied person but to somebody with mobility issues, be them from injury, illness or disability, it can be extremely difficult and limit their access to the museum. Simply moving the ticket desk to the entrance or creating an entrance near the ticket desk would make a huge difference.

On Monday the 29th of August I visited the Brontë Parsonage Museum with my partner and friends. We had been for a picnic at Brontë Falls so a visit to the museum was a nice way to round out the day. Unfortunately the visit was not without problem, largely related to accessibility.

First I should be clear that the Parsonage, museum and exhibits were enjoyable and interesting. The exhibits were beautiful and presented with real care and attention to detail that I appreciated. The setting is, of course, delightful. However, the accessibility issues spoiled my enjoyment and meant that I couldn't fully enjoy the museum.

The Parsonage being on top of a hill was always going to be a difficult approach for me as I have issues with chronic pain and fatigue. This is one of those things you just accept, there's nothing to be done with location. However, I was frustrated to find that the ticket desk was up another slope and in the opposite direction to the Museum entrance. This short extra distance may not seem much to an able bodied person but to somebody with mobility issues, be them from injury, illness or disability, it can be extremely difficult and limit their access to the museum. Simply moving the ticket desk to the entrance or creating an entrance near the ticket desk would make a huge difference.

|

| A written version of this letter has been sent to the Brontë Society |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)